The Mission

Below are extracts from the introduction of The International Spy Film Guide 1945 - 1989 detailing the purpose of The Kiss Kiss Kill Kill Archive and the critera for the choice of films included in the Archive and the book.

The Kiss Kiss Kill Kill Archive

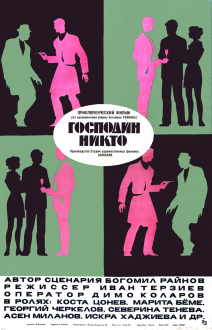

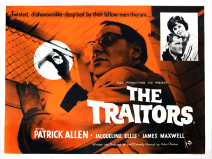

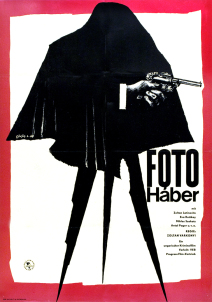

The Kiss Kiss Kill Kill Archive was launched in 2010 to facilitate a project five years in the making—the first ever symposium on spy films hosted by the University of Hertfordshire. This involved an academic event, film screenings and a touring exhibition of spy film posters. The exhibition has subsequently been exhibited in five British public spaces (Hatfield, Aberystwyth, Leeds, St. Albans and London’s Riverside Studios). The project led to the publishing of an exhibition catalogue entitled Kiss Kiss Kill Kill: the Graphic art and Forgotten Spy Films of Cold War Europe, this website resource, the development of a repository of films, artwork and a database that has since evolved into the book The International Spy Film Guide 1945 - 1989.

The International Spy Film Guide 1945 - 1989

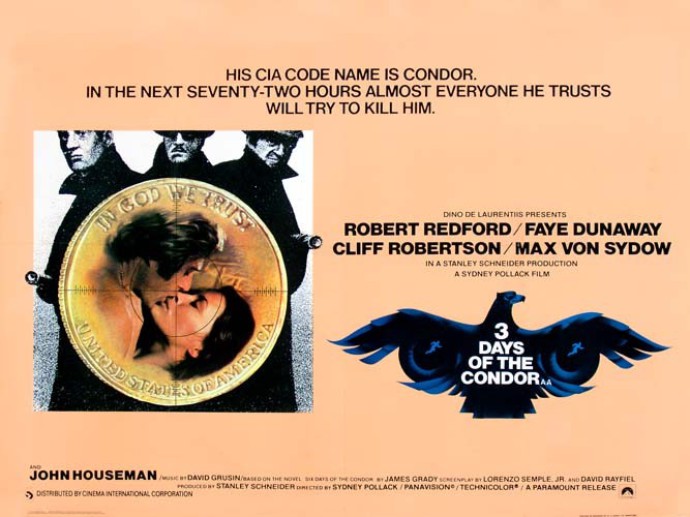

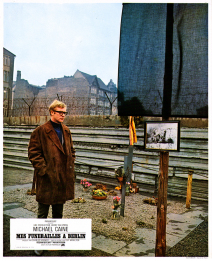

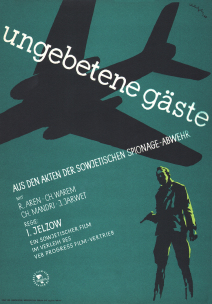

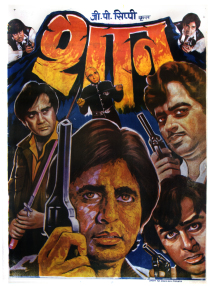

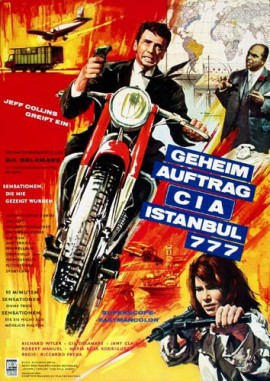

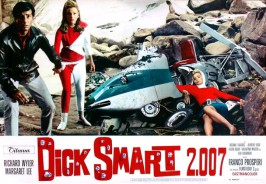

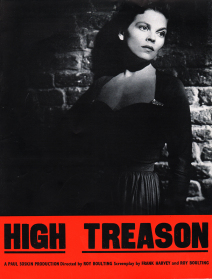

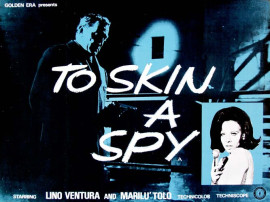

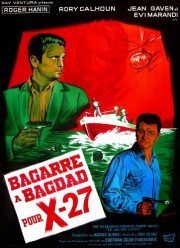

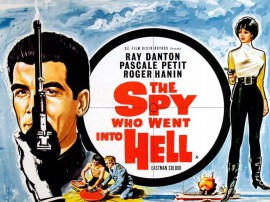

The language barrier as well as the history of separatism inherent in a world of borders has meant dozens of Cold War films have never made it on to the radar. The International Spy Film Guide 1945 - 1989 is here to represent such films. Naturally, I have included all the usual suspects—Bond, Flint, UNCLE, Palmer, Smiley—but these are well known. It is the lost, suppressed, ignored or badly distributed titles I am keen to champion.

Having collated a database of spy films and published several long form reviews on The KKKK Archive website, I felt what was missing was a thorough index of spy films for my selected period—the Cold War. There have been several spy film guides but none that embrace the films of the entire world. I wanted to get away from the western orientated leanings of previous guides. I widened my brief to include everywhere. When I started the project I thought this could only be a few hundred films. This was not to be the case. This strategy and my decision to employ a ‘broadchurch’ approach to the genre led to an ever growing tide of material in languages from all nations boundaries.

By including all foreign languages, my journey into cinematic archaeology has become wider and deeper, revealing many magnificent, lost treasures to share with like-minded aficionados.

Broad-church

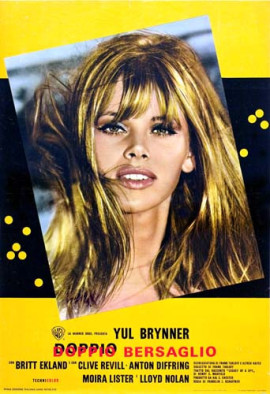

Stella Rimington in her excellent introduction to the 2006 edition of The Spy’s Bedside Book (a compendium of spy stories edited by Graham and Hugh Greene) elucidates on what qualifies as a spy story. Her definition sums up how varied the genre can be. She separates the genre into romantic and realistic stories. The latter she then subdivides into four main strands defined by the real world of spying—military, diplomatic, police and geopolitical. A neat summation. She also suggests that Graham Greene’s inclusion of James Bond in the selection when the book was originally published in 1967 was driven by the character’s massive popularity rather than Bond’s true status as a spy. She asserts James Bond is “no more than a licensed killer”. However, Rimington concedes that in common parlance ‘spy’ implies not only the intelligence-gather but also the action-orientated secret agent.

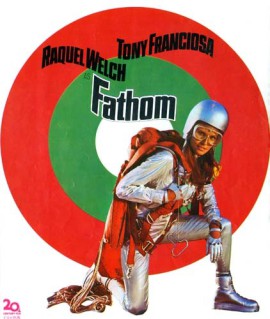

This book could have been called The International Secret Agent Film Guide but ‘spy’ scans better and as Rimington points out, both terms are interchangeable. My definition of a spy film is ‘broad-chuch’. Any agent on a clandestine mission is included here. No-one would dispute the ‘spy status’ of the reinvented Bulldog Drummond in Deadlier than the Male. Richard Johnson’s surrogate superspy character is in fact an insurance agent. With that in mind, I have included agents of all colours as long as they are working undercover and not in uniform—their own nation’s uniform that is. (The rule of war is that soldiers carrying out secret missions are considered spies if they are not wearing the uniform of their country.)

Which leads to the question of war. Whilst the timeline of this book is films produced during the Cold War era (1945—1989) I have decided to include all films that are set during the 20th century. The influence of the World Wars, the Russian Revolution and the second Sino-Japanese War on the Cold War is immeasurable. Indeed the majority of Russian and communist Chinese spy films made during the Cold War era were set during the heroic and uncontentious pre-Cold War era. It is essential to include them. Likewise I decided it was essential to include spy-fi films set in the future. Often these Cold War stories said more about their own era than the future they imagined. Sometimes that was a near-future still within the 20th century time frame, such as the three versions of Orwell’s 1984 and the UFO compilation films which were set in the near-future of 1980.

This spirit of inclusivity extends to all types of feature film. By including compilation films made from TV series and shown theatrically abroad I have been able to include many key spy characters (such as the iconic television spies conjured up by Lord Lew Grade’s ITC productions—Danger Man etc). I have also included the straight-to-video titles that emerged in the 1980s, one-off television movies, the odd theatrical short film and some films that were suppressed and never released. I have allowed a couple of breaches of these already generous boundaries. Such as the inclusion of Ukradená vzducholod which is actually set in 1895 but I took the liberty of including it in order to champion this currently underrated masterpiece.

So my ‘broad-church of spy cinema’ welcomes all creeds and races many of whom will no doubt be considered not really ‘spy’: saboteurs, partisans, mercenaries, ninjas and terrorists all get a look-in as long as their missions are covert. Hitmen (and Hit-ladies as they are called in France) also pose a problem. If they are working for a government agency then they are included. If they are working for the Mafia they are not included. (When it is not clear who is paying the bill as in The Mechanic and L’emmerdeur I have included them because they are good films.)

It is debatable which films belong to a true ‘canon’ of spy films. My feeling is that ‘near cousins’ will be of interest to the aficionado and so inclusivity is better than otherwise. The fashionable, academic term for genre films that do not quite fit in their genre is the Italian term filone. It describes a cycle of films, rather than a genre, that shares the same tropes—stylistic attributes, social context and means of production. (That is why European caper films are often cited as being included in the Eurospy subgenre even though there is not a spy in sight.) I generally need a secret agent to be present in a film for inclusion here. The only non-spy films included are those that belong to a series of spy films. Such as the Three Supermen films where the majority of entries are spy films except one which is a cowboy film. These ‘odd men out’ are included for informational purposes. (When there are many other types of unrelated genres in a series, as in the Santo or Charlie Chan films then only the spy stories are included.)

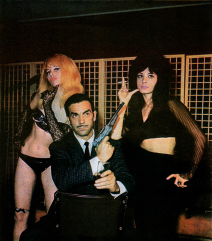

This broad-church also includes films that are blended with other unrelated genres—children’s films, musicals, kung fu, comedy, romance, Blaxploitation, carsploitation, Naziploitation and sexploitation. Which leads to the thorny subject of pornography. Danish director Lars Von Trier would argue pornography represents humanity as much as any film. Spanish director Jesús Franco was, in fact, responsible for the inclusion of spy porn in this book. Franco made 20 spy films in many styles—cine negro, hi-trash, spoof, softcore and full blown hardcore pornography. As all of his spy oeuvre had to be included it seemed logical to review other spy porn. Not as fun a task as you may imagine with most being pretty toxic.

Richard Rhys Davies